In regions like sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East, millions of people lack reliable grid power. Off-grid solar systems offer a strategic solution: they bring clean, 24/7 electricity to remote clinics, schools, farms and homes. For example, a Kenyan farmer doubled his irrigated land and boosted income by ~$2,250 annually after switching from a diesel pump to a solar-powered pump. An on-site solar PV and battery system kept a Nairobi hospital running through a 24-hour blackout, something a diesel generator could only do at high cost and pollution. Likewise, a Lebanese village achieved 24/7 power and cut over $100,000 per year in diesel fuel costs with a local solar microgrid. These data-driven examples show why off-grid solar matters: it spurs economic growth, improves health and education, and builds resilience for critical services.

Building on this strategic value, this guide explains how an off-grid solar system works. We’ll cover the four key components (solar panels, charge controller, battery bank, inverter) and show how each functions to deliver uninterrupted power. We also address local challenges: desert heat, dust, and equipment choices best suited for Africa & the Middle East. Whether you’re an NGO leader, investor, homeowner or small business owner, understanding these components helps plan robust, scalable solar power solutions.

The Impact in Action – A Regional Case Study

Consider a farming cooperative in Kenya that replaced its diesel irrigation pumps with solar-powered pumps. The switch doubled irrigated acreage and enabled multi-cropping – one farmer added cabbage, leafy greens and tomatoes to his land. His annual income rose by about $2,250, and he saved roughly $150 per month in diesel fuel. This illustrates the “why”: solar energy cut operating costs, allowed more reliable irrigation, and directly translated sunlight into higher yields and cash flow.

In the medical sector, reliable power is life-saving. In 2023, Kenya’s largest blackout left many hospitals dark, yet one solar-equipped clinic in Nairobi stayed on without ever firing up a diesel generator. Its on-site solar PV panels and battery bank provided continuous power for lights, vaccine refrigeration and critical equipment. In sub-Saharan Africa, 15% of health facilities lack any electricity connection and only 40% of those with grid access receive reliable power. Off-grid solar systems can close this gap.

In essence, solar energy underpins growth and public services far from the grid. These examples – Kenyan farms, a Nairobi hospital, a Lebanese village – demonstrate the tangible outcomes of off-grid solar: higher productivity, more income, and constant service provision. They set the stage for “how” the technology achieves these results: by converting sunlight into electricity through a carefully sized system of components.

The Four Pillars of Energy Independence: How the System Works

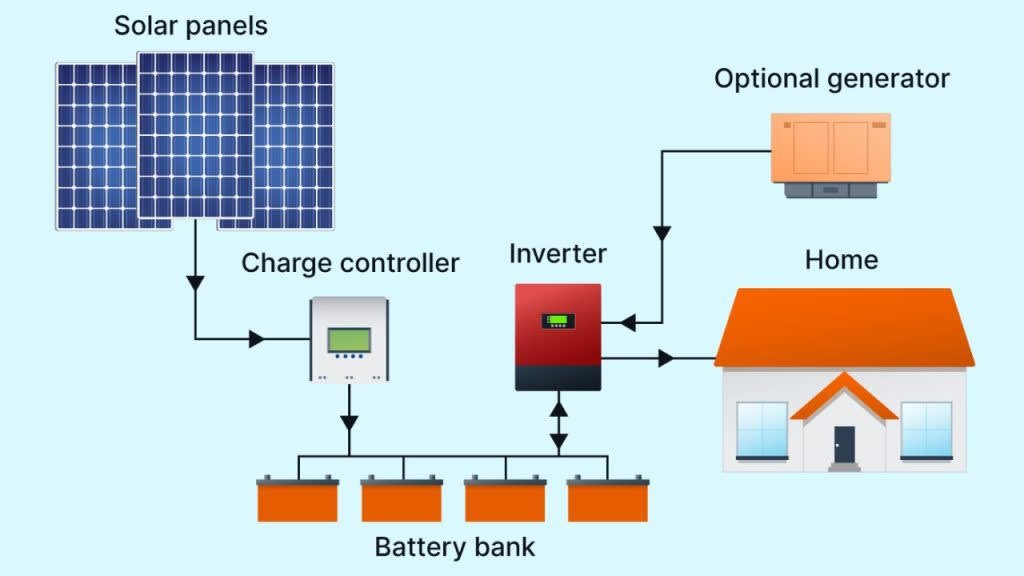

An off-grid solar energy system relies on four core pillars: Solar Panels, a Charge Controller, a Battery Bank, and an Inverter. Each plays a specific role in capturing, storing and delivering power. Below we answer key questions for each component.

How do Solar Panels Generate Power?

Answer: Solar panels convert sunlight into direct-current (DC) electricity.

Solar panels (photovoltaic or PV modules) are made of semiconductor cells (usually silicon) that generate electric current when struck by sunlight.

In simple terms, photons (light particles) hit the cells and knock electrons loose; conductive layers capture these electrons as a flow of DC electricity. Panels are wired into arrays to increase output: more cells and modules yield higher voltage and current. Under full sun, a 1 m² panel might produce 150–200 W, and more efficient monocrystalline panels can reach ~15–20% conversion efficiency in good light.

However, performance depends on conditions. High temperatures reduce output – most panels lose about 0.3–0.5% of efficiency per °C above 25 °C. Desert roofs can exceed 65 °C, so a 17% panel might drop to ~16.4% by mid-afternoon. Dust accumulation is also critical: studies have found dust can cut solar output by tens of percent (up to ~76% in very dusty locations). Thus panels should face the sun (often south-facing in Africa/Middle East), be tilted to match latitude, and be installed where wind or rain can wash them, or cleaned regularly. In short, solar PV modules turn abundant sunshine into DC power, forming the system’s power “generator.”

What is the Charge Controller’s Critical Role?

Answer: The charge controller regulates charging and protects the battery.

Between the panels and the battery sits the charge controller (sometimes called a regulator). Its job is to manage the voltage and current coming from the solar array to ensure the battery charges safely. In direct terms, it prevents overcharging (which can damage batteries) and often prevents excessive discharge.

When panels are under low light (early morning or cloudy) it also optimizes the power flow. Advanced controllers use maximum-power-point tracking (MPPT) to continuously adjust to the PV array’s optimal voltage, harvesting up to ~20–30% more energy than older PWM (pulse-width-modulation) regulators. MPPT controllers are especially valuable for off-grid farms or village systems because they adapt to shading and temperature changes.

In practice, the charge controller keeps the battery voltage within a safe range. It “disconnects” or throttles the PV input once the battery is full, and some designs will prevent the battery from discharging too deeply when panels are not producing. As one solar industry expert notes, high-quality controllers (MPPT or PWM) “preserve the life of your batteries” by performing these regulation tasks.

In an off-grid system, the controller is thus the guardian of the battery bank, ensuring long life and stable charging.

Why is the Battery Bank the Heart of the System?

Answer: The battery bank stores DC energy for use when the sun isn’t shining.

The battery bank is the energy reservoir. It stores all the electricity generated by the solar panels during the day so that power is available at night or during cloudy periods. In other words, the panels might generate 3–6 kWh on a sunny day, and the batteries hold that energy until it’s needed for lights, refrigerators, or any loads after dark. Without batteries, an off-grid home could only use power while the sun shines.

What kind of batteries you choose, and how much capacity you install, is central to system design. Deep-cycle batteries are used so they can be discharged regularly. Lead-acid types (flooded or sealed)

have historically been common, but modern lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) batteries are gaining favor. For example, LiFePO4 units typically endure 3,000–7,000 charge cycles at 80% depth-of-discharge, whereas lead-acid batteries usually survive only a few hundred cycles at 50% discharge. In practice this means LiFePO4 can last 10+ years in solar use compared to 3–5 years for lead-acid.

The choice affects reliability and lifetime cost: a lithium bank needs little maintenance, but lead-acid needs routine water refills, ventilation for hydrogen gas, and will eventually require replacement. Moreover, climate matters. LiFePO4 batteries handle extreme temperatures well: they operate down to –20 °C and up to ~60 °C with little loss in capacity. Lead-acid batteries are more sensitive: they must be kept mostly above 0 °C, as a lead-acid pack can lose ~50% capacity below freezing. In a hot, unventilated shed, a lead-acid bank will age faster. So for Middle East or African sites with high ambient heat, lithium batteries are often advised.

In summary, the battery bank is the system’s heart: it holds the DC energy allowing consistent power flow after sunset. Its capacity (kWh) and type determine how long the lights, pumps or equipment can run without sun, and its health dictates system longevity.

How Does the Inverter Power Your Appliances?

Answer: The inverter converts the battery’s DC electricity to AC for standard appliances.

Most homes and businesses use alternating-current (AC) power, typically 230 V, 50 Hz in Africa/Middle East. But solar panels and batteries produce and store direct current (DC). The inverter bridges this gap by transforming DC into AC. In technical terms, it “inverts” the voltage: for example, it might take 24 V or 48 V DC from the battery bank and output 230 V AC at 50 Hz. This AC output can then run lights, fans, TVs, computers, pumps – essentially any normal appliance.

In practice, an inverter must be sized for the load. A 2 kW off-grid inverter can continuously power up to ~2,000 watts of appliances, with some headroom for start-up surges. Many appliances, like motors, refrigerators, and pumps, draw extra current at start-up, so inverters are often rated 20–50% above the steady power rating they need to deliver. For example, a 500 W fan might need 1,000 W briefly to start, so a larger inverter is chosen. Quality off-grid inverters also include protections like overload, short-circuit, and low-voltage shutdown, and sometimes have built-in chargers for connecting a backup generator.

Efficiencies are high but not perfect: modern pure-sine inverters run at about 90–95% efficiency on average. That means if the battery supplies 1000 W DC, maybe 900–950 W becomes usable AC, with the rest lost as heat. In the energy flow diagram, the inverter is the final step: battery DC ⟶ inverter ⟶ household AC. It completes the journey of solar power from ray to ready-to-use electricity.

Adapting for Success in the Middle East & Africa

Deploying solar in the hot, dusty climates of the Middle East and Africa means choosing and maintaining components carefully. High temperatures and sandstorms can significantly affect performance. The tables below compare common technology choices suited to these conditions. Use the comparisons to select panels and batteries that withstand brutal environments, and follow the actionable advice that follows the tables.

Here is a comparison of solar panel technologies for hot, dusty climates.

| Feature | Monocrystalline Panels | Polycrystalline Panels |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Efficiency | ~15–20% | ~13–18% (somewhat lower) |

| Heat Performance | Loses ~0.3–0.5% efficiency/°C (higher temp coeff) | Loses slightly less in heat (better high-temp behavior) |

| Power Rating | High (per area) – best with limited space | Moderate (per area) – lower output per panel |

| Cost | Higher cost per W (complex single-crystal manufacturing) | Lower cost per W (cast together) |

| Best Use Case | Roof-mount or space-constrained installations; moderate climates | Large flat arrays; extremely hot/dusty sites (less temp sensitivity) |

Tips: Monocrystalline panels give more power per panel, which is good if roof area is tight, but they heat up more and require good ventilation. Polycrystalline panels are cheaper and hold up slightly better in very high temperatures.

In either case, even thin dust layers can cut output by approximately 20–50% or more, so regular cleaning is essential.

Table 2: Comparing Battery Technologies for Off-Grid Energy Storage

| Feature | LiFePO₄ (Lithium Iron Phosphate) | Lead-Acid (Flooded/AGM) |

|---|---|---|

| Cycle Life | 3,000–7,000 cycles at 80% depth of discharge (10+ year life) | Approximately 200–300 cycles at 50% depth of discharge (3–5 year life) |

| Depth of Discharge | Approximately 80% safely usable (draws more of its capacity) | Approximately 50% recommended (to avoid damage) |

| Operating Temp. | –20–60 °C (retains approximately 80% capacity at –20 °C) | 0–40 °C (below approximately 0 °C, it loses up to 50% capacity) |

| Maintenance | Virtually maintenance-free; only needs a built-in Battery Management System (BMS) | Requires regular watering and occasional equalization; must vent hydrogen gas |

| Cost (Initial) | Higher upfront cost, but lower Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) over its life | Lower upfront cost, shorter lifetime, and higher replacement frequency |

Tips: In desert climates, LiFePO₄ batteries are often preferable. They tolerate heat and cold far better than lead-acid batteries, which can lose half their capacity if frozen and overheat above 40 °C. Lithium batteries also avoid venting hydrogen gas, so they can be enclosed safely. Lead-acid batteries are cheaper up front, but remember you will likely replace them multiple times during the lifespan of a single lithium battery.

Climate Adaptation Advice

Dust and heat are the “silent thieves” of power in the Middle East and Africa, so take these proactive steps:

- Install panels at a tilt: A 10–20° angle helps rain and wind clean them. Consider anti-soiling coatings or automated wipers in extremely dusty areas. Research shows that unchecked dust can slash output by tens of percent.

- Clean regularly: In rural settings, aim to wash panels at least every 1–3 months. Even a thin layer of desert dust can cost more energy than is gained by grid-tied sales.

- Choose low-temperature-coefficient panels: Some brands specify a temperature coefficient below –0.35% per degree Celsius. Panels with lower coefficients will lose less output on hot days.

- Provide cooling and ventilation: Mount panels a few centimeters off the roof or ground to allow for airflow. House batteries in shaded, ventilated enclosures to avoid heat soak, as battery life will suffer above approximately 40 °C.

- Oversize slightly: In the design phase, include a margin of 10–20% over calculated loads to offset efficiency losses from heat and dirt. Extra capacity also builds in room for future growth.

- Use MPPT charge controllers: These can recover extra power when panel voltages sag due to heat and dust, making up for losses without needing more panels.

By picking the right hardware and following these guidelines, you can adapt your off-grid solar system to regional realities and maximize its reliability.

From Blueprint to Reality – System Sizing & Scalability

Designing an off-grid solar system combines science and common sense. Here’s a simple framework:

- Estimate Your Load (Energy Needs). List every appliance and its wattage, then multiply it by its hours of use per day to determine its daily energy consumption. For example, to calculate daily usage, you would add up the consumption of each appliance by multiplying its wattage by its hours of daily use. An example calculation would be: four 10-watt lights used for 6 hours, plus one 50-watt fan used for 5 hours, plus one 5-watt phone charger used for 4 hours, which totals approximately 0.6 kilowatt-hours per day. This gives you the daily kWh. Also, note the peak power draws, such as the starting surge of motors.

- Factor in Sunlight (Peak Sun Hours). Determine the average peak sun hours for your location, which is often 5–6 hours per day in much of Africa and the Middle East. Divide your daily load by the sun hours to size the PV array. For a load of 0.6 kWh per day with 5 peak sun hours, you would theoretically need a 0.12 kW array. However, it’s wise to allow for more, such as a 0.2–0.5 kW array, to account for system losses and efficiency factors.

- Size the Battery Bank.

Decide how many days of autonomy you need without the sun (often 1–3 days). Multiply the daily kWh by the number of backup days to get the required battery kWh. For critical uses, two days is common: a 3 kWh/day load needs approximately a 6 kWh battery.

- Choose the Inverter. The inverter’s continuous watt rating should exceed the total expected load. If your largest simultaneous appliance usage is 1,500 W, pick at least a 2,000 W inverter to safely handle surges.

- Check Balance of System. Include a margin (typically 10–20%) over these calculations for safety. Always follow manufacturer datasheets and accommodate wiring and inverter losses. Plan for conduit and mounting for future expansions if the load is expected to grow.

Below are three illustrative system sizes:

| Example System | Typical Loads (Appliances) | Daily Demand | Approx. PV Size | Battery Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Home | 5 LED lights (10W each, 6h/day), 1 ceiling fan (50W, 5h), phone charging | ~0.5–0.7 kWh | ~0.5 kW (e.g., 2×250W panels) | ~1–2 kWh (1-day backup) |

| Small Shop | 3× lights (15W, 8h), 2× fans (50W, 6h), 1 laptop (50W, 6h), mini-fridge (100W, 12h) | ~2.5–3.0 kWh | ~1.5–2 kW (5–7×300W panels) | ~5–6 kWh (2-day backup) |

| Rural Clinic | 4× lights (15W, 10h), 3× fans (50W, 8h), vaccine fridge (150W, 24h), 2× laptops (50W, 8h) | ~5–6 kWh | ~4 kW (≈12×350W panels) | ~10–12 kWh (2-day backup) |

Each row shows a use case, example appliances, daily energy needs, and rough PV and battery sizing. For instance, a basic home may need only a few LED bulbs and minimal electronics, so approximately 0.6 kWh/day can be met by a half-kilowatt array and a small, approximately 1 kWh battery. In contrast, a clinic with refrigeration and computers might need approximately 6 kWh/day, requiring a multi-kW array and a sizable 10+ kWh battery bank to stay operational through cloudy days.

Planning Tips

- Perform the load calculation carefully. Include all essential loads (lights, refrigeration, communications, etc.). Neglecting even small loads can ruin your system’s balance.

- Size components with some overhead. It’s better to have a few unused watts than to cut it too close.

- Design for scalability. Use a controller and inverter that can accept a larger PV array or battery bank if the project grows.

- Engage a qualified solar designer or installer whenever possible, especially for larger systems like those for clinics or communities.

Conclusion

From sunlight to society, an off-grid solar system works as a chain of energy conversion and storage. Sunlight hits the solar panels (PV modules) and is converted into DC electricity. The charge controller regulates this output, optimizing the flow into the battery and preventing damage. The battery bank stores that DC power for later use, effectively serving as the system’s “heart.” When power is needed by appliances, the inverter finally transforms the stored DC into AC electricity that appliances and tools can use. In sequence: sun → PV → DC → controller → battery → inverter → AC → appliance.

This reliable cycle of renewable energy offers resilient power for remote clinics, schools, farms, and villages. In Africa and the Middle East, where grid outages and diesel dependence are common, off-grid solar systems have become a strategic backbone for development. By extracting maximum value from each ray of sunshine—through careful design and maintenance—they provide a lifeline of energy independence.

5 Key Considerations Before Going Off-Grid

- Energy Demand: Calculate your daily kWh and peak loads precisely. Ensure the system meets all essential needs.

- Component Selection: Choose panels and batteries suited to the climate (e.g., high-temperature panels, LiFePO₄ batteries). Use MPPT controllers for the best efficiency.

- System Sizing: Size the PV array and battery bank with a safety margin. Plan for future expansion and include a carbon-free backup for reliability.

- Climate Adaptation: Account for dust and heat. Plan a regular cleaning schedule, place batteries in shaded or ventilated areas, and size the system to offset performance losses.

- Maintenance & Quality: Invest in quality equipment with warranties. Plan routine checks on battery health and controller settings, and train users or technicians on upkeep.

With these factors in mind, decision-makers and users can design off-grid solar systems that truly power their communities, turning abundant sunlight into lasting energy security.