This report provides a systematic and in-depth exploration of sizing a solar system, tailored for two primary audiences: residential homeowners seeking practical guidance and energy sector technical experts requiring engineering depth. The primary objective is to address real-world challenges in determining solar system scale, such as varying energy needs, geographical influences, and economic optimization. By integrating quantitative methods (e.g., load calculations and efficiency metrics) with qualitative analysis (e.g., case studies and trend forecasts), the report offers actionable insights for designing efficient, safe, and compliant systems.

The structure covers historical evolution, current technologies, core components, load analysis, resource assessment, component selection, design principles, performance evaluation, maintenance strategies, economic considerations, safety and regulations, practical examples, and future trends. With a focus on optimizing efficiency and cost while emphasizing safety and regulatory adherence, this report bridges accessibility for homeowners and technical rigor for experts.

1. Introduction

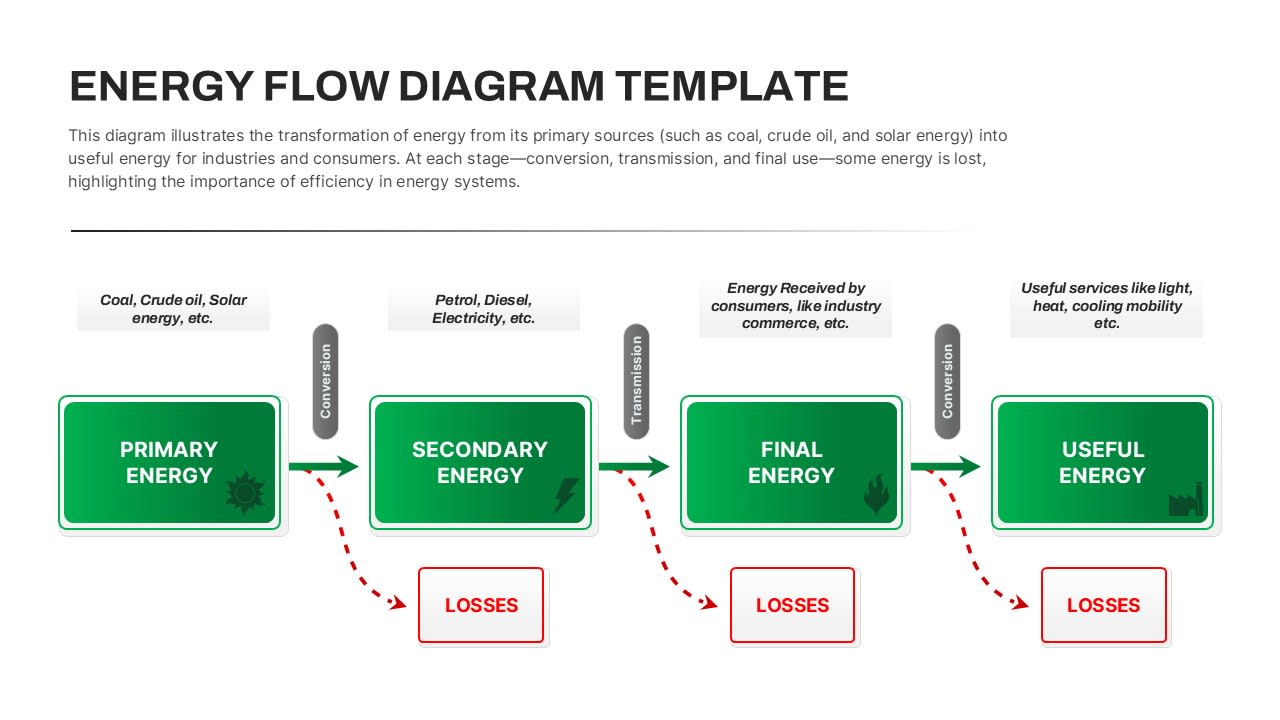

Sizing a solar system involves calculating the optimal capacity of photovoltaic (PV) panels, batteries, and inverters to meet energy demands reliably and cost-effectively. For residential users, this means powering household appliances without excessive upfront costs or energy waste. For technical experts, it entails precise engineering to achieve high system efficiency, often measured by metrics like Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) or Capacity Factor.

Challenges include inaccurate load estimation leading to oversizing (increased costs) or undersizing (power shortages), variable solar irradiance, and evolving regulations. This report addresses these by combining historical context, technical details, and forward-looking strategies, ensuring systems are scalable, economical, and safe.

2. Historical Evolution of Solar System Sizing

Solar technology traces back to the 19th century with Alexandre Edmond Becquerel’s discovery of the photovoltaic effect in 1839. Practical applications emerged in the 1950s with Bell Labs’ silicon PV cells, initially for space exploration (e.g., Vanguard 1 satellite in 1958). Residential adoption grew in the 1970s amid oil crises, with early sizing methods relying on basic formulas like daily energy need divided by peak sun hours.

By the 1980s, grid-tied systems introduced net metering, shifting sizing from off-grid autonomy to economic payback. The 2000s saw advancements in modeling software (e.g., PVWatts by NREL) enabling precise simulations. Today, AI-driven tools incorporate real-time data for dynamic sizing, reducing errors by up to 20% compared to manual methods. This evolution underscores a shift from rudimentary estimates to data-driven optimization, addressing past issues like inefficient battery storage in early systems.

3. Basic Components of a Solar System and Their Functions

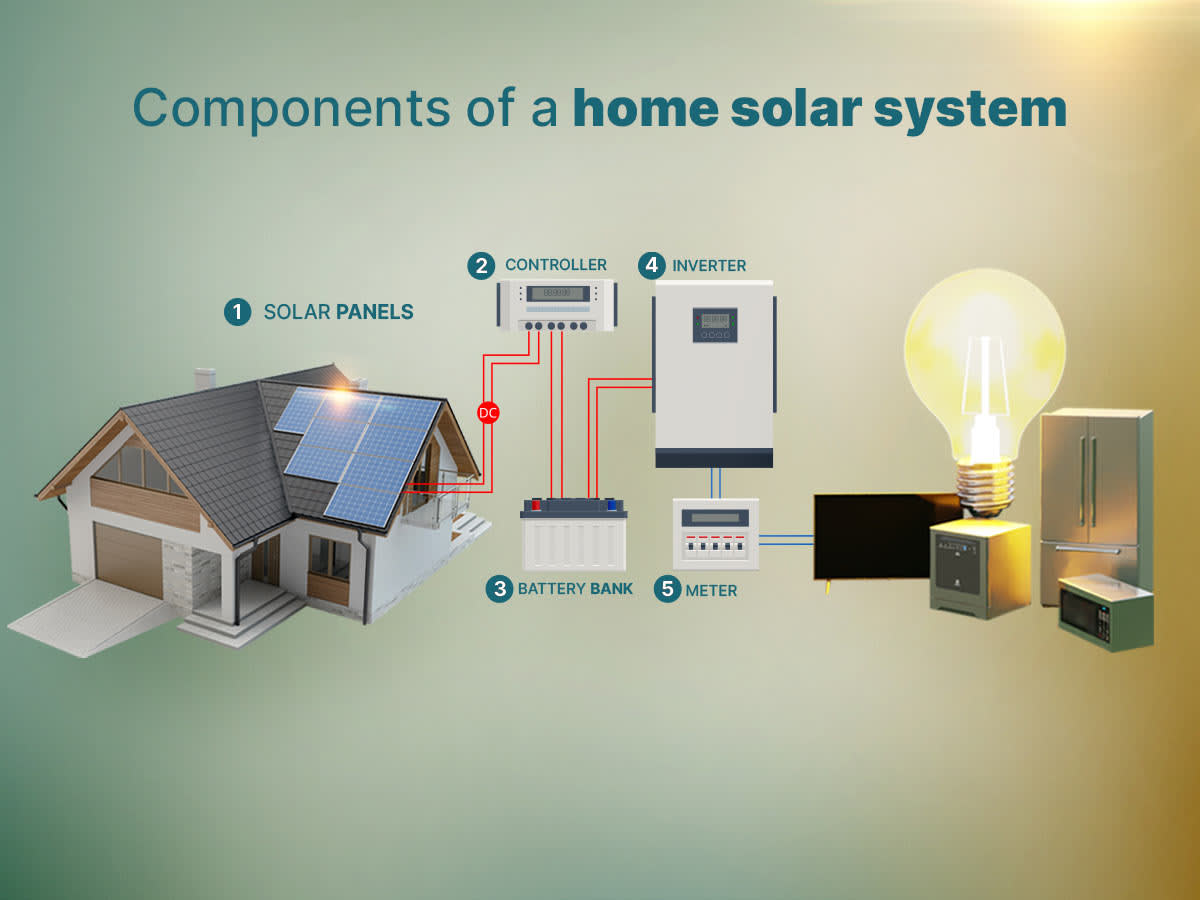

A solar system comprises four core elements: PV panels, inverters, batteries (for storage), and charge controllers.

- PV Panels: Convert sunlight into DC electricity via the photovoltaic effect. Monocrystalline panels offer high efficiency (15-22%) but higher cost; polycrystalline (13-16%) are more affordable. Function: Primary energy generation.

For homeowners, think of them as “solar roofs” powering lights. For technical experts, it’s important to note that the power output in Watts depends on the panel’s efficiency. The efficiency, represented by the Greek letter eta, is calculated by dividing the output power by the product of the solar irradiance (power per unit area from the sun) and the panel’s surface area. The result is then multiplied by 100 to express it as a percentage.

- Inverters: Convert DC to AC for household use. String inverters are cost-effective for homes, while microinverters optimize per-panel performance. Their function is to ensure compatibility with household appliances. Efficiency is typically between 95-98%, but derating factors, such as temperature, can reduce performance. For example, efficiency often drops by 0.5% for every degree Celsius above 25°C.

- Batteries: Store excess energy for later use. Lithium-ion batteries are the dominant technology, offering a round-trip efficiency of 90-95% and a depth of discharge (DoD) up to 90%. This is significantly higher than lead-acid batteries, which have a DoD of 50-80%. Their primary function is to provide backup power during outages or periods of low sunlight.

- Charge Controllers: Regulate the charging of batteries to prevent overvoltage and damage. MPPT (Maximum Power Point Tracking) types are more advanced and can boost energy output by 15-30% compared to older PWM (Pulse Width Modulation) controllers.

These components form a cohesive system. Proper sizing is critical to ensure balance; for instance, the panel array’s output must match the inverter’s capacity to avoid “clipping,” where potential energy generation is lost.

4. Load Demand Analysis and Electricity Usage Pattern Assessment

Accurate system sizing begins with quantifying the property’s energy needs. For homeowners, this can be as simple as listing all appliances and estimating their daily usage (e.g., a refrigerator might use 1.5 kWh per day). Technical experts, on the other hand, conduct detailed audits using tools like energy monitors.

Quantitative Method: The average daily load, represented as E_load, is determined by summing up the energy consumption of all individual appliances. The consumption for each appliance is found by multiplying its power rating in kilowatts by the number of hours it is used per day. For example, consider a family that uses lights (100W for 5 hours), an air conditioner (1kW for 4 hours), and miscellaneous devices (500W for 2 hours). The total daily energy load is calculated by adding the consumption of each: 0.1 kW multiplied by 5 hours, plus 1 kW multiplied by 4 hours, plus 0.5 kW multiplied by 2 hours, resulting in a total of 5.5 kWh per day. It is also crucial to factor in peak demand—the maximum power required when multiple appliances run simultaneously (e.g., 2 kW)—for correct inverter sizing.

Usage Patterns: It is important to assess seasonal variations in electricity use, such as spikes from air conditioning in the summer versus heating in the winter. A qualitative analysis involves profiling the electricity consumption by categorizing it. This includes the base load, which consists of always-on devices like routers, and the variable load.

which includes intermittent high-draw items like electric vehicle (EV) charging. Specialized tools like HOMER software can simulate these usage patterns, predicting annual consumption with up to 95% accuracy.

The primary challenges in this stage are overestimation, which inflates system costs, and underestimation, which can lead to power blackouts. To mitigate these risks, a common solution is to add a 20-30% buffer to the calculated load to account for future growth and unforeseen needs.

5. Solar Resource Assessment and Geographical Influences

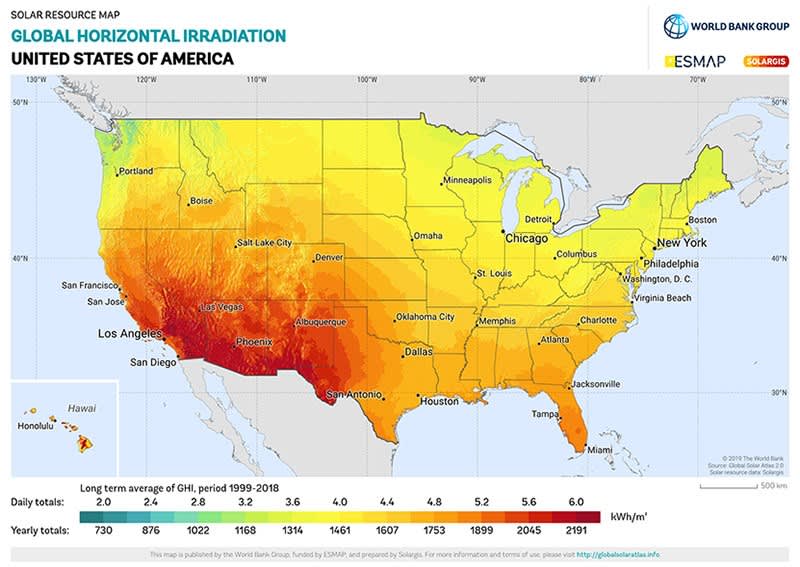

The amount of solar energy available, known as solar potential, varies significantly by location and directly impacts system sizing. It is essential to use solar insolation data, typically measured in kilowatt-hours per square meter per day (kWh/m²/day), from reliable sources like NASA’s POWER database.

Quantitative Assessment

A key metric for this is Peak Sun Hours (PSH), which standardizes the average daily solar irradiance. It is calculated by dividing the total daily solar radiation by a standard irradiance of 1 kilowatt per square meter. For example, a location like Phoenix, Arizona, may have a PSH of 6, while Seattle, Washington, has a PSH of around 3.5.

The required system size in kilowatts can then be estimated using a formula: divide the average daily energy load (E_load) by the product of the Peak Sun Hours (PSH) and the overall system efficiency. For instance, with a daily load of 5.5 kWh in Phoenix (PSH of 6) and a system efficiency of 80% (0.8), the required system size is calculated as 5.5 divided by the product of 6 and 0.8, which equals approximately 1.15 kW.

Other geographical factors also play a critical role. For example, a site’s latitude affects the optimal tilt angle for the panels; the ideal angle is often set to the site’s latitude, with an adjustment of plus or minus 15 degrees to optimize for seasonal changes in the sun’s path. Furthermore, shading from trees or nearby buildings can reduce a system’s output by 10-50%. Experts use Geographic Information System (GIS) tools for detailed, site-specific modeling that incorporates factors like albedo (surface reflectivity) and local microclimates.

Qualitative Assessment

On a qualitative level, urban areas often present challenges related to permitting and space constraints, while rural sites typically offer more space but may suffer from higher energy losses during transmission over long distances.

6. Technical Specifications and Selection Principles for Solar Panels

Solar panels are selected based on key criteria such as wattage, efficiency, and durability. While homeowners often prioritize the cost per watt—which typically ranges from $0.50 to $1.00 per watt—technical experts also evaluate performance metrics like the temperature coefficient. This is particularly important in hot climates, as panel efficiency decreases with heat, typically at a rate of negative 0.3% to negative 0.5% for every degree Celsius rise above standard test conditions.

Selection Principles

A core principle is to match the panel array to the energy load. For example, a 2 kW system could be built using five 400-watt panels. A quantitative approach involves calculating the required number of panels by dividing the total desired system size (in watts) by the wattage of a single panel. It is also wise to consider the panel’s degradation rate, which is typically 0.5% to 1% annually, to ensure long-term performance.

Types of Panels

Modern options like bifacial panels can capture reflected light from their rear side, which can boost energy yield by an additional 10-20% depending on the surface beneath them.

Selection principles also emphasize durability, with homeowners and experts alike looking for robust warranties (typically 25 years) and key certifications, such as IEC 61215 for hail resistance.

7. Technical Specifications and Selection Principles for Energy Storage Batteries

Energy storage batteries are crucial for ensuring system reliability, especially in off-grid applications or as backup power. Lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) batteries are often preferred for their longevity, offering over 6,000 charge cycles compared to the 2,000 to 4,000 cycles typical of other lithium-ion chemistries.

Specifications

Key technical specifications to consider include:

- Capacity (kWh): The total amount of energy the battery can store.

- Depth of Discharge (DoD): The percentage of the battery’s capacity that can be safely used. A higher DoD means more usable energy.

- C-rate: The speed at which the battery can be charged or discharged relative to its capacity.

To determine the required battery size, a common formula is used. The total battery capacity is calculated by multiplying the average daily energy load (E_load) by the desired number of days of autonomy (the number of days the system can run on battery power alone) and then dividing by the battery’s Depth of Discharge (DoD).

For example, to cover a daily energy need of 5.5 kWh with two days of autonomy, using a battery with a 90% DoD (or 0.9), the calculation would be: the product of 5.5 kWh and 2 days, divided by 0.9, resulting in a required battery size of approximately 12.2 kWh.

Selection

When selecting a battery, homeowners often prioritize systems with user-friendly monitoring apps. Technical experts focus on performance metrics like round-trip efficiency. This efficiency is calculated by dividing the energy output from the battery by the energy input required to charge it, then multiplying by 100 to get a percentage. Key selection drivers include optimizing for cost (typically between $200 to $400 per kWh) and prioritizing safety features, such as the inherent thermal runaway prevention found in LFP batteries.

8. Typical Electricity Load Classification and System Design Guidance

A crucial step in system design is to classify electricity loads. These are typically categorized as essential loads, such as refrigerators and lights, which must remain powered during an outage, and non-essential loads, like a pool pump, which can be shed. This classification informs the design strategy, whether it’s an off-grid system built for complete autonomy or a hybrid system designed to provide grid support and backup for critical needs.

As general guidance for a typical 2,000-square-foot home with an average daily consumption of 30 kWh, a solar panel array sized between 10-15 kW and a battery bank of 20-30 kWh would be appropriate. For a more quantitative approach, experts use the load factor, which is calculated by dividing the average load by the peak load. This metric helps in right-sizing inverters to handle demand efficiently without being excessively large.

Furthermore, incorporating smart controls for demand-side management can shift energy use to off-peak times, potentially reducing the required system size by as much as 15%.

9. System Performance Evaluation and Long-Term Maintenance with Scale Adjustment Strategies

System performance should be evaluated using key metrics. The Performance Ratio (PR) is a primary indicator, calculated by dividing the system’s actual energy output by its expected theoretical output. An ideal PR typically falls between 75% and 85%. Continuous monitoring with Internet of Things (IoT) sensors provides the real-time data needed for this evaluation.

Long-term maintenance is vital and includes routine tasks like cleaning solar panels quarterly and inspecting batteries annually. For scale adjustment, modular system designs are advantageous, as they allow for straightforward expansion, such as adding more panels to accommodate a forecasted 20% growth in energy load.

Advanced strategies involve using predictive analytics to account for long-term factors like panel degradation. This ensures the system continues to meet performance targets, such as maintaining a Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) below $0.10 per kWh.

10. Economic Optimization and Efficiency Enhancement

Economic considerations are a primary driver in system sizing. A simple and effective metric is the payback period, which is calculated by dividing the total initial system cost by the annual savings on electricity bills. For instance, a $15,000 system that generates $2,000 in annual savings will have a payback period of 7.5 years.

Efficiency can be further enhanced by optimizing panel tilt and minimizing shading, which can lead to gains of 5-10%. Financial incentives, such as government tax credits, also significantly reduce the net cost and shorten the payback period.

For technical experts, economic optimization involves more advanced financial modeling. They often calculate the Net Present Value (NPV) to assess long-term profitability. This value is determined by summing the cash flows over the system’s lifetime, with each cash flow discounted to its present value. The formula involves dividing each period’s cash flow by one plus the discount rate, raised to the power of the corresponding time period. The ultimate goal is to achieve an Internal Rate of Return (IRR) greater than 10%, which signals a financially attractive investment.

11. Safety Considerations and Regulatory Constraints

Safety is non-negotiable in solar system design and installation. Key measures include:

- Grounding: Proper system grounding is essential to prevent electric shocks.

- Arc-Fault Protection: Arc-fault circuit interrupters (AFCIs) must be used to detect and mitigate dangerous electrical arcs, which are a primary cause of solar-related fires.

Regulatory compliance is equally critical. All systems must adhere to the National Electrical Code (NEC), which specifies requirements such as rapid shutdown capabilities to de-energize panels quickly for firefighter safety. Additionally, installers must follow all local building and electrical codes. For homeowners, it is imperative to hire certified installers. For technical experts, the focus is on ensuring all components are UL-listed, verifying their compliance with established safety standards. Failure to comply with these regulations can lead to severe consequences, including voided warranties, hefty fines, and significant safety hazards.

12. Practical Case Studies

Examining practical case studies helps illustrate the application of these principles in the real world.

- Residential Case: A California family with a daily energy load of 20 kWh, located in an area with 5.5 Peak Sun Hours (PSH), installed a 5 kW system with a 10 kWh battery. The total cost after incentives was $18,000, resulting in a six-year payback period. A key challenge was partial shading from nearby trees, which was effectively addressed by using microinverters to optimize the output of each individual panel.

- Expert Case: A Texas engineer was tasked with designing a 50 kW commercial system. By leveraging advanced technologies like bifacial panels and AI-powered optimization tools for precise load modeling, the design achieved an excellent 88% Performance Ratio (PR). This sophisticated approach led to a 15% cost saving compared to traditional design methods.

13. Future Trends and Developments

The solar industry is continuously evolving, with several key trends shaping its future. Technological advancements include the development of perovskite solar cells, which promise efficiencies exceeding 25%, and the integration of Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) technology, allowing electric vehicles to serve as dynamic energy storage.

Artificial intelligence will play an increasingly important role, enabling real-time adjustments to system sizing and energy management, which could reduce energy waste by up to 20%. Economically, costs are projected to continue their decline, potentially reaching as low as $0.3 per watt by 2030. These trends, combined with supportive policy shifts toward net-zero emissions, are expected to significantly expand residential solar adoption.

14. Conclusion: Strategic Insights and Operational Value

Successfully sizing a solar system requires a careful balance of technical precision and practical considerations. When done correctly, it yields substantial economic benefits, such as electricity bill reductions of 20-50%, and significant environmental gains, with each installed kilowatt saving approximately one ton of carbon dioxide emissions annually.

For homeowners, the journey can begin with simple energy audits. For experts, it involves leveraging sophisticated simulation tools to achieve optimal performance. This report provides a comprehensive toolkit for designing resilient and scalable systems, underscoring the importance of proactive maintenance and strict regulatory adherence. By addressing the challenges holistically, both homeowners and technical experts can make informed decisions that contribute to a sustainable and self-sufficient energy future.