1. Introduction: The Philosophy of the Trusted Energy Advisor

In many African communities, access to reliable electricity is a pressing challenge: roughly 600 million people on the continent still lack power. Solar technicians can no longer afford to be mere salespeople; they must become trusted energy advisors who solve real problems. This means valuing field pragmatism (finding what works in local conditions), socio-economic insight (understanding customer needs and budgets), and ecosystem building (strengthening local skills and networks). As one solar industry trainer puts it, a trusted advisor “does more than just selling a product… understands customer needs and offers solutions that make sense”. In practice, this means listening carefully, building long-term relationships, and using data-driven methods rather than guessing sales pitches.

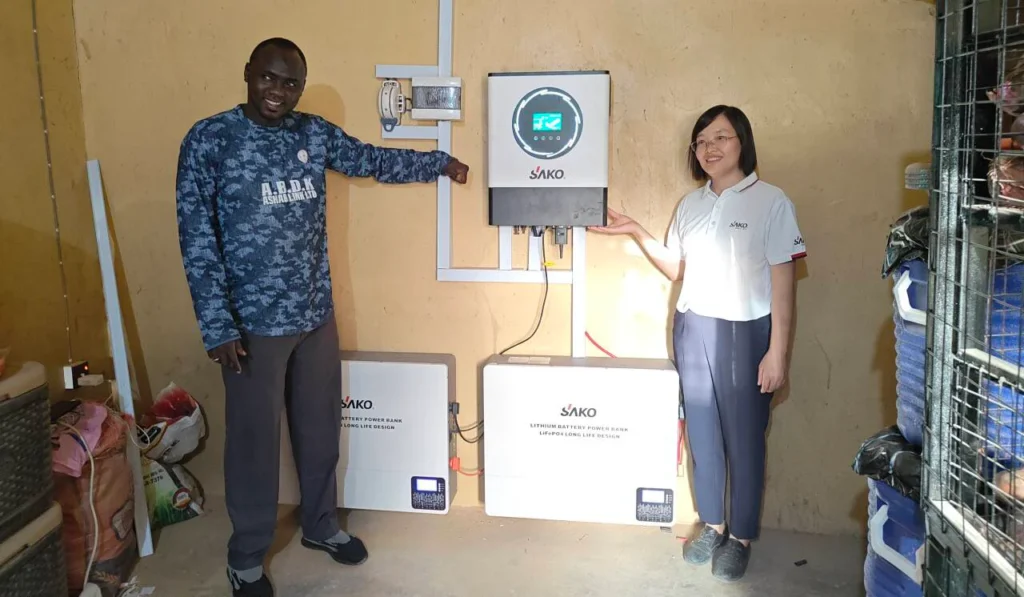

Recent reports underline the need for this shift. Africa’s green energy transition is hindered by a major skills gap. Many technicians lack updated training in modern, off-grid solar design, and even college graduates often require significant retraining. Programs like Tanzania’s Barefoot College “Solar Mamas” train rural women as solar technicians through hands-on learning, transforming them into local energy experts. Similarly, local solar companies and NGOs are building “agent networks” of field advisers to reach underserved rural markets. These initiatives show that when local teams gain trust and skills, they can manage installations and maintenance independently.

Key Insight: To be credible, a solar advisor must respect the customer’s reality (budget, lifestyle, reliability needs) and work within it. This means treating system design as a consultation: perform thorough load analysis on-site, explain trade-offs, and co-create a solution. The advisor’s role extends beyond installation into education: teaching clients how to use and maintain their systems, and how to plan for future needs. In short, building energy services is as much about people and processes as it is about hardware. Training this mindset is as crucial as teaching technical skills.

2. The Five Pillars of Comprehensive Load Analysis

To design a system that truly meets a client’s needs, we use five interlocking “pillars” of load analysis. Each pillar mixes technical measurement with understanding the user’s behavior and priorities.

2.1 Static Load Inventory

Start by listing every electrical appliance the household or business uses (or wants to use). For each item, record its power rating (in watts) and mode of use. Common African household appliances include LED lights (5–15W each), phone chargers (5–10W), radios (~5–20W), TVs (30–100W), small fans (30–75W), refrigerators (150–300W running; plus a several-hundred-watt starting surge), and irons or mixers (1000–1500W). Don’t forget surge currents: many motor-driven loads (fridges, deep freezers, water pumps) draw two to three times their running watts at start-up. The inverter must handle these surges, so this inventory is critical. Water pumps, welding machines, and induction cookers, common in some areas, can have very high surges.

Practical Tip: In the field, have a checklist or form of typical appliances, copy it, and mark which are present. Talk with the clients to discover less obvious loads (a market vendor’s freezer, a clinic’s ventilators, a school’s computers). Aim to catch all loads, even small ones like phone chargers, because they add up.

2.2 Dynamic Usage Profile

Next, develop a Daily and Seasonal Usage Profile for those appliances. This means estimating how long and when each device runs. For example, members might watch TV four to five hours each evening, lights are on during dark hours, the fridge may cycle 24/7 (with a compressor kicking in a few times per hour), and phones charge for a couple of hours mostly at night. Seasonality matters: for example, fans may run longer in hot afternoons or evenings, and in some regions rainy seasons mean less solar charging.

Use “time-of-use worksheets” to chart each hour of the day and note which loads run during that hour. This shows daily peaks and valleys. For instance, in many off-grid systems the main evening peak is from lights and TV. Bowling down the total daily energy (watt-hours per day) is the first step to sizing energy and storage, but understanding when that energy is used identifies the worst simultaneous demand. What happens if everyone charges phones at 9pm? Or if all lights, fan, and TV run at 8pm?

2.3 Load Prioritization Tiers

Not all loads are equally important, especially under limited generation or storage. Establish priority tiers with the client:

- Tier 1 (Essential): Life-supporting or critical loads (lights after dark so children can study, a medical fridge in a clinic, phone for emergency calls, water pump for drinking water).

- Tier 2 (Important): Comfort and business loads (fan in the afternoon kitchen, radio/TV for news, sewing machine or workshop tools for income generation, small freezer for perishables).

- Tier 3 (Optional/Luxury): Heavy or non-essential loads (iron, large water heater, air-conditioning, large rice-cooker permanently on).

Discuss these tiers with the client. The client may agree, for example, that if energy is low one month, they will limit use of the Tier 2 loads (e.g. postpone ironing or limit TV hours) to reserve battery for Tier 1. This consultative prioritization empowers clients to make choices about trade-offs rather than being surprised by a dead battery. It also guides system sizing: you might design the system to handle all Tier 1 loads plus some Tier 2 load only when abundance allows. Listing tiers helps focus on a realistic system that users will actually benefit from.

2.4 Concurrency Factor & Risk Assessment

Calculating power needs involves understanding concurrency – the chance that multiple loads run simultaneously. In practice, seldom do all lights, fans, pumps and appliances run at full power together. For example, not every lamp will be on or every phone charging at the same instant. We often apply a diversity or concurrency factor (e.g. 0.6–0.8) to the sum of individual loads to avoid gross over-sizing. This factor can be estimated from observation: over a week of interviews/visits, note if large loads ever coincide (fridge, pump, and wash machine might, for example, be staggered because of human habits).

Risk assessment: Be cautious – underestimating concurrency can cause inverter overload. A pragmatic designer might compute the worst-case (100% concurrency) but then adjust it downward based on evidence. Any reduction should come from observed behavior: e.g., “In this rural household, the corn grinder (1500W) is only used during midday mess-house production, not during evening TV time.” Always discuss “what if” scenarios: “If all these loads did run at once, the battery would not last as long; is that acceptable?” The advisor must ensure that recommended margins cover expected realities, perhaps by adding a safety margin (e.g. design for 0.75 concurrency factor on large loads).

2.5 Future Growth & Scalability Margin

Finally, consider future growth. Even rural customers often expect some increase in energy use over time (perhaps acquiring a new appliance, adding family members, or expanding a shop). Technicians should build in a scalability margin. A rule of thumb: design 20–30% larger than today’s calculated needs if budget permits.

For example, if today’s loads total 3 kWh/day, plan batteries for ~3.6–4 kWh. This headroom lets clients purchase one more 12V battery or LED light later without junking the system.

For a pragmatic check: ask “what will you add in the next 3–5 years?” If the answer is “maybe another light and eventually a fridge,” include that from the start. It’s often more cost-effective to size slightly larger up-front than to pay remobilization fees for an upgrade later. However, be honest about cost: explain the value of growth margin versus the upfront expense.

Summary of Pillars: The five pillars form a cycle: inventory loads (pillar 1), record how and when they run (pillar 2), ask clients to rank them (pillar 3), consider how likely they run together (pillar 4), and plan for what might come (pillar 5). Training should give students tools – load-survey forms, interview scripts, even smartphone apps – to systematically apply each pillar in the field.

3. The Pragmatic Data Collection Toolkit

Robust load analysis relies on gathering real data. Technicians should be equipped with a toolkit of methods:

- Art of the Interview & Observation: A structured questionnaire guides the conversation. Sample questions: “List all electrical items you use daily/weekly.” “How many hours per day do you run each lamp/TV/fan?” “Which appliances are most important if power is low?” Use open questions to avoid yes/no answers. For example: “Walk me through your day from 6 AM to 9 PM – what gadgets do you turn on and when?” While interviewing, observe the home: count lights, inspect switches, hear a hum of a fridge compressor, note if someone has a generator or solar panels already. Watching actions (someone plugging a charger every night at 8 PM) can reveal habits the client might forget to mention.

- Targeted Measurement: When possible, use a portable power meter or clamp meter. Measure the actual wattage of opaque loads – for instance, old refrigerators often list nameplate amps, but a quick clamp-meter test will show real running current (often higher). Measure lamps (LED vs incandescent), fans, and especially motors (pump or compressor) to confirm your estimates. A digital meter that logs watt-hours (some smartphone gadgets or cheap “Kill-A-Watt” devices) can record daily use of a load. For example, ask the client to use the device on their fridge for a day (if they have a spare appliance plug) to get Wh/day. Measurement data can reveal surprises (a 100W max TV might draw only 30W on average during video).

- Collective Intelligence – Shared Databases: No advisor needs to start from zero. Use or contribute to shared templates of typical loads for similar customers. Over time, programs or companies often build libraries: e.g., “Rural household in Kenya (3-room) – 4 bulbs (10W each, 6 hrs), 1 TV (40W, 4 hrs evening), 1 fan (50W, 5 hrs afternoon), 1 phone charger (5W, 3 hrs).” Refer to previous case files, use any published load profiles, and update them with your own measurements.

Platforms like GOGLA or local NGO networks may have load surveys for the region. When training local trainers, collect anonymized data from each site visit into a central database. Teaching advisors to leverage others’ experience helps small organizations avoid dead reckoning every time.

In practice, teach this toolkit in workshops with role-playing, such as practice interviews, and field trips. Distribute sample questionnaires and train on consistent note-taking. Emphasize cultural sensitivity; for example, politely requesting to monitor someone’s energy use requires building trust. An advisor might say, “With this meter I’ll see how much your fan actually uses; it helps us save you money by not oversizing.”

4. From Analysis to Sizing

Once the data are collected and analyzed, the advisor translates it into system specifications: battery capacity (kWh) and inverter size (kW). This section outlines the calculation process in practical steps.

4.1 Battery Sizing (Energy Storage in kWh)

Step 1 – Daily Energy Needs: Sum the energy use of all loads from the inventory over a typical day. For each appliance, the formula for this calculation is: Daily Watt-hours equals the appliance’s Power in Watts multiplied by the Hours of use per day.

For example, four lamps at 10 Watts each used for 5 hours would consume 200 Watt-hours (10 x 5 x 4). A refrigerator averaging 150 Watts while running for a total of 8 hours of compressor time would consume 1200 Watt-hours per day. After totaling all loads, let’s assume a total of 5000 Watt-hours (5 kWh) per day.

Step 2 – Depth of Discharge (DoD) & Autonomy: Choose a suitable maximum Depth of Discharge, which is usually 50% for lead-acid batteries to maximize their lifespan. Next, decide on the desired days of autonomy, which is the number of days the system can run without recharging. For a backup system in Lagos, where the grid is available sporadically, one day of autonomy might be sufficient. For a rural off-grid home in Kenya with frequent rain, two to three days of autonomy may be necessary.

For our example, with a goal of 2 days of autonomy and a 50% DoD, the required battery energy is calculated. The Daily Watt-hours (5,000) is multiplied by the Days of Autonomy (2) and then divided by the DoD (0.5), resulting in a total need of 20,000 Watt-hours, or 20 kWh.

Step 3 – Battery Configuration: Choose a nominal battery voltage, commonly 12V or 24V. Then, convert the energy requirement from Watt-hours to Amp-hours (Ah). At 12V, 20,000 Wh would require approximately 1,667 Ah. With a more typical 24V system, the requirement is about 833 Ah. If you select 12V batteries to create a 24V system, you would wire them in series pairs. For example, using 200 Ah, 12V batteries, each series pair provides 200 Ah at 24V. To reach the 833 Ah target, you would need five of these pairs connected in parallel, for a total of 1000 Ah (5 strings x 200 Ah). This bank would consist of 10 batteries in total (5 parallel strings of 2 batteries each). The final storage capacity is 24,000 Wh (24 kWh), which meets the 20 kWh usable target while accounting for losses and aging.

Throughout this process, add a margin for battery aging and temperature, as colder climates can reduce capacity. For simplicity in training, the core formula is taught as: Battery Capacity in Amp-hours equals the Daily Watt-hours multiplied by the Days of Autonomy, with the result divided by the product of the System Voltage and the Depth of Discharge. Also, stress the importance of rounding up to the next available battery size or adding an extra string if needed.

4.2 Inverter Sizing (Power in kW)

Step 1 – Determine Continuous Load: Add up the maximum wattage of all loads that may run at the same time, typically Tier 1 loads plus some from Tier 2. For example, a backup system in Lagos might need to power lights (40W), a TV (40W), a PC charger (60W), and a small fridge (300W) simultaneously, for a total of about 420W continuous. Always check that the inverter’s continuous rating exceeds the sum of these concurrent loads. In practice, select the next standard inverter size above your calculated sum.

Step 2 – Surge Capacity: Identify any high-surge loads within the group of appliances that run simultaneously. Common surge loads include refrigerators, which can draw approximately three times their running power at startup, and pump motors. The inverter’s surge, or peak, rating must exceed the total of the continuous load plus these surges.

If our example refrigerator surges to 900W while the other active loads (lights and TV) consume 420W, the total momentary power required is 1320W. Therefore, the inverter’s surge capability, often specified as its peak wattage for one second, must be at least 1320W. Many inverters with a 1000W continuous rating offer a 2000W surge capacity, which would be sufficient.

Step 3 – Voltage Compatibility: The inverter must be matched to the battery bank’s nominal voltage, such as 12V, 24V, or 48V. It is also important to consider the inverter’s efficiency and its continuous output. For instance, a 1000W inverter connected to a 24V system might draw approximately 50A at full load. This is calculated by dividing 1000W by 24V, which equals about 42A, and then adding current to account for inefficiencies. This means the battery and wiring must be rated to safely handle that current. A good practice is to ensure the inverter’s maximum draw does not exceed 13–20% of the battery bank’s capacity to avoid stressing the batteries. For example, a 1000W inverter on a 24V system drawing around 42A continuously would require a battery bank of at least 200–300 Ah to keep the discharge rate under 20%.

Step 4 – Final Selection: Choose an inverter model that meets the continuous and surge power requirements, matches the system voltage, and preferably provides a pure sine wave output for sensitive electronics. Trainees should understand that inverter costs often increase in distinct steps. If the calculated size is on the borderline between a 1 kVA and a 2 kVA unit, it is wise to consider whether managing loads occasionally is more practical than allocating a larger budget. It is generally acceptable to slightly oversize the inverter to accommodate future growth or unexpected loads. Conversely, if the budget is very tight and a slightly smaller inverter is chosen, the client must be educated on the importance of staggering the use of large appliances.

These sizing principles are consistent with off-grid design guides, which state that an inverter must be able to meet the continuous demand of all running loads while also accommodating short-term surge demands. An advisor should always double-check worst-case scenarios. For example, they should ask, “What happens if the kettle (1500W) is turned on while the TV (100W) is on and the refrigerator’s motor kicks in?” Although a high-power appliance like a kettle is typically excluded from critical load design, having this conversation helps manage expectations.

5. Scenario-Based Applications

To illustrate these principles, consider three realistic case studies:

5.1 Scenario A: Urban Backup System in Lagos, Nigeria

Background: Lagos experiences highly unreliable grid supply, leading many urban households to use backup solar-plus-battery systems alongside generators. This case study focuses on a house in a Lagos suburb with partial daytime grid power and frequent evening outages. The family’s Tier 1 needs include four 10W LED bulbs, a 40W LED TV, a 60W laptop, mobile phone charging, and a small 200W refrigerator used for storing medicine. Tier 2 loads include a 50W ceiling fan for hot afternoons and an occasional 1000W iron. Tier 3 loads like air conditioning or a water heater are not expected to run on this system.

Analysis: An interview reveals that the lights run for about five hours per night, the TV for three hours in the evening, and the refrigerator runs steadily. Phones require about 20 Wh per day for charging, and the laptop uses around 180 Wh daily. The evening peak load is approximately 120W. The total daily energy consumption is the sum of lights (200 Wh), TV (120 Wh), refrigerator (240 Wh), laptop (180 Wh), phones (40 Wh), and a fan for two hours (100 Wh), which totals approximately 880 Wh per day. Adding a 30% margin brings the daily requirement to 1.3 kWh.

Sizing: The system is designed for at least one day of autonomy, as the grid is expected to return the next day. To calculate the battery size for a 12V system with a 50% Depth of Discharge (DoD), the daily energy need (1300 Wh) is divided by the voltage (12V) and then by the DoD (0.5), resulting in a requirement of about 217 Ah. A single 12V 120Ah battery is insufficient. A better configuration would use two 6V 200Ah batteries wired in series (creating a 12V 200Ah unit) and then two of these units in parallel for a total of 400 Ah. This provides 4.8 kWh of total storage (2.4 kWh usable), safely covering about two days. For the inverter, continuous loads are around 280W. However, the refrigerator’s surge is about 600W. A 1000W (1 kVA) pure-sine inverter is selected to provide sufficient headroom and easily cover the surge. This also allows for future expansion, such as adding another TV or a small freezer.

Advisory Note: Trainees should be taught to advise clients that Tier 2 loads like the fan should only be used when the battery is healthy, and Tier 3 loads like the iron should only be run when the generator is active. While the designed battery can run everything for about two days, the family should be encouraged to conserve energy if the grid outage lasts longer than a day. The Lagos context suggests that finances might allow for future upgrades, but this core design meets the family’s immediate needs.

5.2 Scenario B: Rural Off-Grid Home in Western Kenya

Background: This family lives several kilometers from the grid in a Kenyan village and relies entirely on solar power. Their key Tier 1 loads include five small 8W LED lamps, chargers for three 5W phones, a 10W radio, and a 100W refrigerator. Tier 2 loads consist of a 40W TV used for about four hours in the evening, a 60W laptop used intermittently, and a 50W ceiling fan used at night during the hot season. There are no Tier 3 loads initially.

Analysis: Field measurements indicate the following daily energy consumption: lights contribute 240 Wh, phones add 15 Wh, the radio uses 30 Wh, the refrigerator’s compressor consumes 200 Wh, the TV uses 160 Wh, the laptop adds 120 Wh, and the fan consumes 200 Wh. The total daily energy usage is approximately 965 Wh, or about 1 kWh per day. Applying a 20% safety margin brings the design target to 1.2 kWh.

Sizing: To ensure two days of autonomy during the rainy season, the required battery capacity in amp-hours is calculated. The daily energy need of 1200 Wh is divided by the system voltage of 12V, and the result is then divided by the maximum Depth of Discharge of 0.5, yielding a required capacity of approximately 200 Ah. A 12V 200Ah deep-cycle battery provides 2.4 kWh of storage, sufficiently covering the two-day requirement. For the inverter, the worst-case concurrent load includes lights, a running refrigerator, a laptop, and charging phones, for a continuous load of about 320W. The refrigerator’s startup surge could reach 600W. Therefore, a 600W continuous inverter with a 1500W surge rating is a suitable choice. This also covers simultaneous use of lights, a TV, and a tablet. A pure-sine wave model is recommended to protect the refrigerator’s compressor.

Outcome: The system might include a modest PV array of approximately 300W to recharge the battery daily. Because productive activities are minimal, the system is small but carefully tuned. In training, it is important to emphasize to students how this family’s strict priority on lighting and phone charging drives a compact design. If the family later buys a 200W sewing machine, the system would need to be upgraded, serving as another teachable point on planning for growth.

5.3 Scenario C: Productive-Use System in Northern Ghana

Background: A small cocoa farm compound uses solar for both household and productivity loads. Tier 1 needs include six 10W lights, phone charging, a 200W freezer for beans, and a 125W grain grinder used for about two hours per day. Tier 2 loads include a 150W sewing machine for tailoring, two 40W TVs that are rarely on simultaneously, and four 11W LED CFLs in a harvesting shed used in the early mornings. Tier 3 consists of an occasional 500W electric rice cooker for community events.

Analysis: The daily energy usage is calculated by summing the contributions of each appliance: lights use 300 Wh; the kiosk freezer consumes about 1000 Wh; phones add 20 Wh; the grain grinder uses 250 Wh; the sewing machine adds 150 Wh; the TVs contribute 240 Wh; and the shed lights use 176 Wh. This results in a total of approximately 1,936 Wh per day, which is rounded up to 2 kWh for design purposes. Given the business-critical nature of the loads, a three-day autonomy period is targeted to protect against crop spoilage during extended cloudy weather.

Sizing: Using a three-day autonomy period and a 50% Depth of Discharge, the total battery capacity is calculated. For a 12V system, this would require a very large 1000 Ah capacity. This suggests that a higher voltage, like 24V, would be more efficient for reducing wiring losses. At 24V, the calculation yields a more manageable 500 Ah requirement. This could be achieved with eight 12V 250Ah lead-acid batteries, configured as two parallel strings of four batteries in series, creating a 24V, 500Ah bank with 12 kWh of total storage (6 kWh usable). For the inverter, the worst-case concurrent loads include the freezer motor’s surge, the grinder, lights, and the sewing machine, summing to a continuous load of approximately 935W with a surge requirement of about 1200W. A 1200W to 1500W pure-sine wave inverter would be selected to cover all loads and protect sensitive electronics.

Advisory Notes: The farm advisor is trained to tell the client that the 500W rice cooker should only be run when the battery is full or supplemented by a generator, because its single-burst demand could strain the system. Also, because freezers store valuable produce, the design emphasizes the heavy freezer load, ensuring at least three days of autonomy as a hedge against downtime. This case underscores how productive uses significantly multiply energy demands, as data shows that electricity consumption for business activities can often be triple that of typical household use. It also highlights the importance of building community trust: this farmer will likely pay more and expects a reliable system, so the advisor stresses quality components like deep-cycle batteries and a robust inverter, along with a maintenance plan that includes periodic battery checks and usage logs.

6. Conclusion: Building the Professional Ecosystem

A strong curriculum must conclude by reinforcing that no advisor thrives in isolation. Solar professionals should be encouraged to share knowledge and continue learning. This involves forming local communities of practice: regular meetups where technicians discuss tricky cases, update their appliance wattage lists, and troubleshoot design hurdles. These could be supported by NGOs or vocational schools hosting “solar clinics,” much like agricultural extension services. Digital platforms may also help, for example, through WhatsApp groups or simple databases where load surveys can be pooled.

Master trainers should emphasize that continuous professional development is vital. Technologies and market conditions evolve rapidly, with new developments like BLDC fans and smart energy management apps. Technicians should be encouraged to attend refresher workshops, webinars, and conferences. Ideally, certification should require periodic renewal to demonstrate that the advisor stays up-to-date on best practices.

By cultivating an ecosystem of local experts and mentors, the program will multiply its impact. Trainees become trainers in their turn, propagating pragmatic methods like the five pillars and data-collection skills further into their communities. Over time, a network of trusted advisors can raise the quality and reputation of solar services continent-wide. In this way, the curriculum does more than teach calculations—it helps build a self-sustaining professional culture.

Key Takeaways: The era of one-size-fits-all sales pitches is ending. This curriculum trains technicians to become energy consultants who analyze real-world needs through five robust pillars, collect precise field data, and translate that into reliably sized systems. Each system design is validated by community-relevant case examples—whether a Lagos rooftop or a Ghanaian farm—ensuring concepts are applied, not just theoretical. By embedding this knowledge in a network for continual learning, we move closer to the goal: empowered African communities with dependable solar power, guided by local trusted experts.